For more than 210 years, investors have grown comfortable with the full faith and credit guarantee provided by the U.S. government. The guarantee has survived depressions, panics, a civil war, two world wars, and numerous alterations to the Constitution and political landscape. But what if we turn the clock back further, to when our country was a fledgling start-up with no prescribed budget or system of taxation and the term “full faith and credit” were just words without the unwavering value of today?

It just so happens that the 1803 Louisiana Purchase was the event that solidified the unconditional guarantee of the U.S. government to repay its bond holders. The bonds involved helped secure one of the largest land deals in American history, financed Napoleon Bonaparte’s conquest of Europe, and represented the first time that American securities were issued on an international stage. In other words, modern American high finance was born in 1803.

The Background.

For much of the 1790s, France’s Napoleon Bonaparte waged war throughout Europe. By the turn of the century, the fighting lulled and an eerie, yet short-lived peace arose for a brief period from October 1801 to May 1803 between Napoleonic France and King George III’s British empire. Napoleon’s desire for empire and the mutual mistrust between the two world powers fed an increasing appetite for the raising of larger armies and navies. The raising of forces required men and material, but above all else, it first required hard cash. This was especially true for France whose purse strings were stretched putting down a costly slave revolt in Haiti. As Napoleon considered ways in which to bankroll his ambitions, he looked across the Atlantic to his holdings in the new world, specifically the port of New Orleans and the Louisiana Territory, both of which he had recently acquired through a secret October 1, 1800 deal with the Spanish. Although Napoleon had previously signed a peace treaty with the United States, rumors of the secret retrocession of Louisiana from Spain to France sparked anxiety in Washington City (today Washington, D.C.). When Secretary of State James Madison received a copy of the secret deal in November of 1801, the rumors were confirmed. Over the course of the next two years, President Thomas Jefferson prepared to counter an impending French presence (with dreams of empire) in the Mississippi Valley and port of New Orleans. Adding to the political uncertainty for the new nation was Jefferson’s fear that a French presence in the American south would prompt a British invasion, putting the world’s two super powers in combat on America’s border. President Jefferson and Secretary of State Madison aimed to arrive at a diplomatic solution. In 1802 they dispatched Minister Robert Livingston to France to ascertain whether the French would be congenial to selling the territory and port and, if so, at what price. When negotiations stalled, Jefferson dispatched James Monroe as a special envoy to France to assist Livingston in hammering out the details of the deal.[1] Operating on a shoe string budget, Monroe sold his china and furniture to raise travel funds, asked a neighbor to manage his properties, and sailed for France on March 8, 1803.[2]

Ultimately, events outside the control of either Monroe or Livingston forced Napoleon’s hand. After a year of fighting on Saint Domingue, the French army was depleted and cash poor. By April 1803, Napoleon had little choice but to divest himself of the Louisiana Territory. Monroe and Livingston received word from the French Minister of Foreign Affairs Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgard. Reporting to Secretary of State James Madison on the morning of April 11, an astonished Livingston wrote that “Mr. Talleyrand asked me this day, when pressing the subject, whether we wished to have the whole of Louisiana. I told him no, that our wishes extended only to New Orleans & the Floridas…He said that if they gave New Orleans the rest would be of little value, & that he would wish to know ‘what we would give for the whole’.”[3]

Financing the Deal.

The question for the United States government was how to raise the necessary funds to complete such an unprecedented deal. As the American side speculated about France’s asking price, they surmised that such a large sum could neither be taken out of revenue nor be borrowed from U.S. investors alone. For the valuation of Louisiana, the U.S. government turned to the two most formidable banks of the day, Hopes of Amsterdam and Barings Bank of London. Both houses were friendly towards the new American nation. Thinking of the deal in its earliest stages, Sir Francis Baring, the bank’s senior partner said, “We all tremble at the magnitude of the American account.”[4] Soon both banks found themselves in the center of a financing operation, advising both the United States and the French government. The banks’ representatives, Alexander Baring of Barings and Pierre Labouchère of Hopes, arrived in Paris in April 1803 to join America’s negotiators and Napoleon’s minister, François de Barbé-Marbois. Because of the long journey time between London, Amsterdam, and Paris, and because of the prospect of letters being intercepted, they were granted full power to do a deal autonomously. First, the bankers and representatives persuaded the French government to scale down its asking price for the territory from 100 million French Francs to 80 million French Francs (the equivalent of $15 million USD) or about four cents an acre. Second, Alexander Baring proposed that financing the deal could only be achieved through a massive American bond issuance. In other words, the Americans would take on debt to provide them with the sum needed to carry out the deal. Of the $15 million required, $3.75 million USD (FF20 million) would be covered by the U.S. government assuming responsibility for certain French damages already owed to U.S. citizens, while the remaining sum – $11.25 million USD (FF60 million) – would be paid to France in the form of a massive delivery of Treasury bonds.[5]

The Bonds.

The bonds issued to France were the first U.S. securities floated in the international markets. The bonds carried a 6.00% coupon payable in semi-annual interest payments and held maturities that redeemed between 1819 and 1822, or 15 to 20 years from issuance. With the delivery of the bonds, France relinquished its control over Louisiana and the Port of New Orleans to the United States. However, interest payments alone would not fund Napoleon’s preparations for war with Britain. The bankers quickly recognized this and endeavored to purchase the bonds from the French government. This accomplished two things: first, it provided a cash lump sum to Napoleon and secondly, it transferred ownership of the American debt to Barings Bank and Hopes of Amsterdam. Always after a good deal, the bankers negotiated the price of the block bond purchase to a sum of 52 million French Francs or about 86.5% of the face value of the bonds. In other words, Barings and Hopes, bought the bonds at a discount knowing they could sell them on the secondary market for a premium (price above par or face value) or profit from those tranches they decided to keep in house when the principal payments came due.[6]

The bankers found investors eager to buy the bonds in London, Amsterdam, and Washington. Much like today, they wrote a prospectus to advertise their bonds on the secondary market. A copy of the prospectus that circulated London at the time still survives today (Figure 1).[7]

Figure 1. American Louisiana Bond Prospectus circulated in London in 1803 by Barings Bank

How risk was managed during this period is largely unknown, but a form of underwriting was common at the time. Physically transporting the bonds took weeks and was not without risk (the ship-bound journey from Washington to Paris was eight weeks). Letters and correspondence were often sent in triplicate in case the ships that carried them sank. For Barings and Hopes, a snippet of surviving correspondence reveals that as early as November 1803, they had disposed of $5 million worth of the bonds on the secondary markets in London and the Netherlands and another $1.5 million of the bonds back in the U.S., leaving them about $4.75 million of the American debt on their own balance sheet.[8]

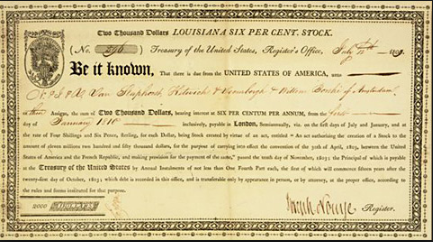

By 1804, the negotiators were discharged from France, their job complete. As the interest payments started rolling into the coffers of Barings and Hopes, France and the British Empire went to war. Thus, a British bank financed a cash deal to pad the pockets of its nation’s sworn enemy…it’s not personal I suppose, just business! In terms of the return on their investment, Barings and Hopes turned a hefty profit. Looking at the entire affair from a yield to maturity perspective for the bonds held and not immediately sold at a premium, Barings’ yield to maturity would have been around 7.29%. This doesn’t account for the massive profits they reaped by selling the bonds at an immediate premium on the secondary market. An example Louisiana bond still survives as part of the National Archives and Records Administration (Figure 2).[9]

Figure 2. Louisiana Bond Certificate (original dimensions, 10.5 inches by 5.5 inches). Transcript: “Be it known, That there is due from the UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, unto, N. & J. & R. van Staphorst, Ketwich & Voombergh & William Borski of Amsterdam, or their Assigns, the sum of Two Thousand Dollars, bearing interest at SIX PER CENTUM PER ANNUM, from the first day of January 1810 inclusively, payable in London, Semiannually, viz. on the first days of July and January, and at the rate of Four Shillings and Six Pence, sterling, for each Dollar, being Stock created by virtue of an act, entitled ‘An Act authoring the creation of a Stock to the amount of eleven millions two hundred and fifty thousand dollars, for the purpose of carrying into effect the convention of the 30th of April, 1803, between the United States of America and the French Republic, and making provision for the payment of the same,’ passed the tenth day of November, 1803; the Principal of which is payable at the Treasury of the United States by Annual Instalments[sic] of not less than One Fourth Part each, the first of which will commence fifteen years after the twenty-first day of October, 1803; which debt is recorded in this office, and is transferable only by appearance in person, or by attorney, at the proper office, according to the rules and forms instituted for that purpose.”

The Interest and Principal Payments.

The purchase of Louisiana represented a 19% increase to the public indebtedness of the United States government which stood at $80 million when Thomas Jefferson assumed the office of the presidency in 1801. Because Americans were mistrustful of their new government levying taxes (they had overthrown the British two decades earlier for the same reason), the U.S. government and Treasury had limited debt servicing capacity, primarily relying on federal customs tariffs for revenues. In a time when the United States didn’t have taxes (like we know them today), to dispose of the $675,000 due to its Louisiana bondholders on an annual basis in interest alone, the government sold land and collected customs revenue at its ports (primarily New York City) to ensure their timely payments. The acquisition of the Port of New Orleans added another $200,000 a year in customs royalties as well.[10] Looking at the whole picture, in 1804 when the first round of interest payments came due, the Federal customs revenues were $10.48 million, and the total government revenue was $11.83 million. Put more succinctly, the financing of the Louisiana Purchase represented 95% of the country’s annual revenue![11] The United States operated on a shoestring budget but paid its way in an increasingly complex world of finance. Treasury Secretary Albert Gallatin’s judicious budget administration meant that no additional taxes had to be levied upon citizens to pay off the bonds. It is also important to note that at the time, the U.S. was considered an emerging market, making its debts a speculative or high-risk investment.

The Legacy.

For the United States, the whole transaction was an incredible success. From a physical standpoint, the purchase doubled the landmass of America. On the world stage, a European threat to America’s sovereignty was removed without bloodshed. In the universe of high finance, U.S. credit in the international markets was established by the Louisiana bonds as their interest payments were rendered with impeccable regularity and investor principle returned on time or even early in some cases. From Amsterdam to London to Philadelphia, regular citizens saw their principle investments in the American Louisiana bonds redeemed on time. Thus, in the eyes of everyday investors, America’s guarantee to repay its debts was established. American bond holders gained a new level of faith in their government to honor their debts even as America plunged into war with Great Britain in the War of 1812. As a principle architect of the deal, Robert Livingston wrote, “We have lived long, but this is the noblest work of our whole lives. From this day the United States take their place among the powers of the first rank.”[12] The investors of today, who take for granted the safety of their Treasury notes, bills, and bonds, lest not forget when America’s credit worthiness was speculative at best and how the actions of a handful of men used finance and diplomacy to change the course of history and the international securities markets for the better.

[1] Mullen, Pierce. “Financing the Purchase.” Fort Clatsop Holidays, Discovering Lewis & Clark. Accessed February 16, 2019. http://www.lewis-clark.org/article/316.

[2] Harriss, Joseph A. “How the Louisiana Purchase Changed the World.” Smithsonian.com. April 01, 2003. Accessed February 16, 2019. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/how-the-louisiana-purchase-change….

[3] Robert R. Livingston to James Madison, Paris, April 11, 1803, American State Papers, Foreign Relations, 2, 552.

[4] “Exhibition: The Louisiana Purchase.” The Baring Archive: Exhibitions. 2008. Accessed February 16, 2019. https://www.baringarchive.org.uk/exhibitions/louisiana_purchase/3.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Museum of American Finance, Louisiana Purchase prospectus, 1804. Credit: The Baring Archive. https://www.moaf.org/exhibits/barings-in-america/lousianaprospectus.

[8] “Exhibition: The Louisiana Purchase.” The Baring Archive: Exhibitions. 2008. Accessed February 16, 2019. https://www.baringarchive.org.uk/exhibitions/louisiana_purchase/3.

[9] Mullen, Pierce. “Financing the Purchase.” Fort Clatsop Holidays, Discovering Lewis & Clark. Accessed February 16, 2019. http://www.lewis-clark.org/article/316.

[10] “Louisiana Purchase.” The Lehrman Institute. Accessed February 16, 2019. https://lehrmaninstitute.org/history/louisiana-purchase.html#aftermath.

[11] “Fortis and ING Celebrate Louisiana Purchase 200th Anniversary Bond Transaction.” Insurance Journal. June 03, 2004. Accessed February 16, 2019. https://amp.insurancejournal.com/news/international/2004/06/04/42895.htm.

[12] Spencer, Jesse A. History of the United States: From the Earliest Period to the Administration of James Buchanan; in 3 Vol. Vol. 3. New York: Johnson, Fry, 1858, 38.